Adaptive Action Sports Announces Partnership with WHITESPACE for the 2024/25 Snowboard Season

Adaptive Action Sports (AAS) announce a new partnership with WHITESPACE for the 2024/25 snow season.

By Michelle Bruton

When Kiana Clay moved from Texas to Colorado to train in adaptive snowboarding full-time with the Adaptive Action Sports team, the many sacrifices she made—including working multiple jobs to support herself and temporarily living out of her truck—were in service of an overarching goal: compete in the Beijing 2022 Paralympics.

But Clay may not have the opportunity to compete in her disciplines of bordercross and banked slalom at the upcoming Paralympics—not because of anything she’s done or because her level of riding isn’t high enough; the 27-year-old just won the Dew Tour adaptive banked slalom competition at Copper Mountain earlier this month.

Rather, the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) has not included Clay’s class—SB-UL, or female snowboarders with an upper-limb impairment—as a discipline at the upcoming Paralympics due to a pool of competitors it has deemed too small.

The women have world cup and world championship events though World Para Snowboard, with athletes represented in most participating countries—including a large contingent in China, host to the fast-approaching Games—but with the interruption of Covid-19, not enough women competed in these events to convince the IPC to include the class at the Beijing Games.

So Clay has started a petition she plans to submit to the IPC imploring the committee to add her class to the program for the Beijing Paralympics.

“I’m really just trying to be the voice of adding this new category and creating more opportunities not only for upper-limb women, but adaptive sports in general” Clay told me.

Bullied for being “bossy” and “loud” growing up, Clay—who from a young age has been drawn to anything that goes fast—says she now considers those two of her best qualities because they enable her to advocate for her sport without fear.

Clay did not compete in snowboarding professionally prior to the accident that left her without the use of her right—and dominant—arm when she was 12 years old. She was competing in motocross at the time and sustained a neck injury when she crashed during a race, impeding the use of the arm. A car accident soon after confirmed that she would be without its use permanently.

It wouldn’t be until college that Clay was able to get back on a dirtbike, but when she did, she had a fortuitous meeting at a race with adaptive snowboarder and Paralympian Mike Schultz, who, too, raced dirtbikes and snowmobiles competitively before a snowmobile accident resulted in the amputation of his left leg above the knee.

Schultz had started snowboarding competitively after meeting Daniel Gale and Amy Purdy, founders of the Copper Mountain-based Adaptive Action Sports. Clay told Schultz she hadn’t been on a snowboard since she was a kid, but he recommended she reach out to Gale and Purdy.

Though she hadn’t snowboarded as an adult until four years ago, Clay has become the country’s top-ranked adaptive female snowboarder with an upper-limb impairment.

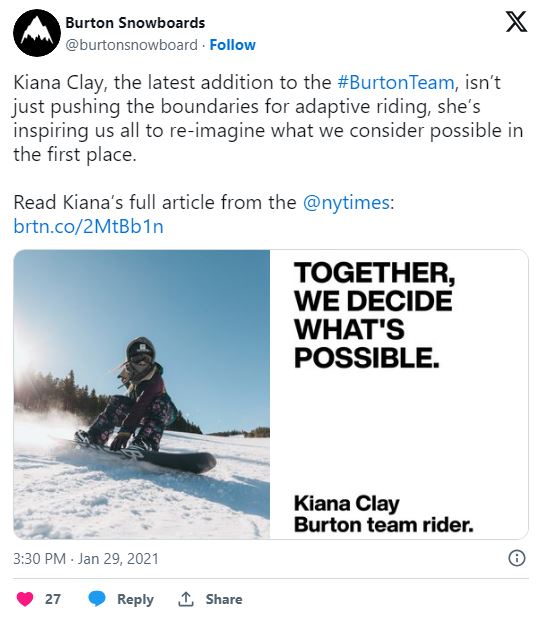

In November 2020, Clay signed with Burton Snowboards, working with Innovative Prototyping Engineer Chris Doyle and the rapid prototype team to provide real-world feedback on the brand’s step-on technology, which has revolutionized Clay’s riding.

Without having to waste valuable minutes strapping and unstrapping her bindings, which is difficult to do with one arm and having to reach across her body, Clay can simply step onto her board and she’s off to win another race.

Clay’s mission to appeal to the IPC has the support of her sponsors Burton, MicrosoftMSFT +1.1% and Anon, as well as Adaptive Action Sports, Gale and Purdy.

But everyone understands the petition is a long shot; Clay continues to train full-time for a Paralympics in which she may not compete.

“We always knew from the beginning that the likelihood of [the petition] working was probably a fraction; that said, I think it was important to do to make sure that that voice was heard,” Gale told me. “The biggest thing we can do as an organization that is centered around growing athletes through our pipeline is to grow more UL-category athletes. And the bigger we can make that classification within the World Para Snowboard circuit, then it will become a class at the Games.”

And it’s not just Clay’s class that has been affected. Purdy is a three-time Paralympic medalist across her two disciplines of banked slalom and bordercross, but her SB-LL1 class—which the IPC defines as “significant impairment in one leg, for example an above knee amputation, or a significant combined impairment in two legs, for example significant muscle weakness or spasticity in both legs”—has been eliminated from the Beijing Paralympics.

Clay’s class has yet to be included on a Paralympic program because not enough women competed at the previous world championship—though it’s now a large class and undoubtedly has enough women to appear on the Paralympic program.

But Purdy’s class has been eliminated altogether due to her competitors either recently retiring or getting injured.

“There are women who won medals at the last Games who now can’t compete because they eliminated my class,” Purdy said. “We need more women representing what’s possible and inspire more women to get involved.”

One possibility would be having all female adaptive snowboarders compete in the same category; at the Sochi 2014 Paralympics, SB-LL1 and SB-LL2 (“an impairment in one or two legs with less activity limitation”) women did compete together. When the SB-LL1 pool of women grew, it became its own class for PyeongChang 2018.

It would technically be a disadvantage for the SB-LL1 women with a more significant impairment to compete against the SB-LL2 class, but many of them would rather compete together in one class that not compete at all. However, the IPC has rejected that idea multiple times.

And for Clay’s class, there is a clear cyclical problem that female snowboarders seeing others with their disability competing at the Paralympics would be the ultimate visibility to encourage more women to get involved…but the IPC won’t create a SB-UL class until more women get involved.

“It’s really frustrating, but at the same time it’s been a really cool journey because the connections that I’ve made and making adaptive sports even more vibrant in the community has been awesome. So the petition has actually brought a lot more good,” Clay said.

“I just remember being that little girl with an upper-limb disability wondering if certain things were possible, and I don’t want a little girl watching the Paralympics and not seeing her category represented and making her feel that she doesn’t have a place in this world or have her feel that she’s not capable of doing something because she has an upper-limb disability. That’s kind of my main goal.”

Originally Published by Forbes Magazine

Adaptive Action Sports (AAS) announce a new partnership with WHITESPACE for the 2024/25 snow season.

Enter to Win an Ultimate Experience to attend the Dancing with the Stars Season Finale in Los Angeles alongside former contestant and AAS co-founder, Amy Purdy!

WE’RE OPENING OUR DOORS AND YOU’RE INVITED! Come check out our new headquarters, meet our athletes, and learn how you can get involved. There will

Interested in joining us? Fill out the information below and we’ll send you more information.